Rainbow

with Egg

Underneath and an Elephant

Shoot The Moon

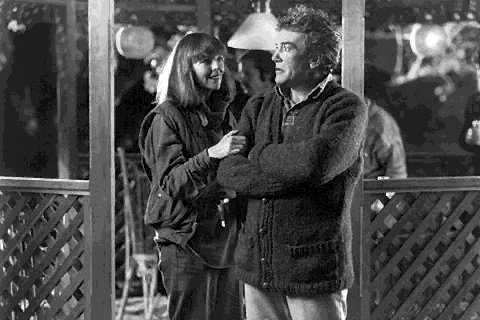

Shoot the Moon

U.S.A., 1981

Director: Alan Parker

MONTHLY FILM BULLETIN

Vol. 49, No.581

June 1982

by TOM MILNE

Cert--AA. dist--United International Pictures. p.c--MGM. exec. p-- Edgar J. Scherick, Stuart Millar. p--Alan Marshall. p. manager--Ned Kopp. unit p. manager--Nancy Giebink. asst. d--Raymond L. Greenfield, Francois X. Moullin. sc--Bo Goldman. ph--Michael Seresin. col--Metrocolor. 2nd Unit ph--(San Francisco) Joe M. Winters. camera op--John Stanier, (San Francisco) Jan D'Alquen. ed--Gerry Hambling. p. designer--Geoffrey Kirkland. a.d--Stu Campbell. set dec--Bob Nelson, Doug Von Koss. set dresser--Clarence H. Walker III. sp. effects--Dick Albain. graphics--John Gorham. Landscape co-ordinator--George Zimninsky. songs--"All I Have to Do Is Dream" by Boudleaux Bryant performed by Juice Newton, "I Can't Tell You Why" by Schmit, Henley, Frey, performcd by The Eagles. "Play with Fire" by Jagger, Richards performed by The Rolling Stones; "Still the Same" by and performed by Bob Seger. cost. design--Kristi Zea. cost--Mary E. Still, Bill Browder, Cathleen Edwards. make-up--Richard Sharpe, Don Le Page. sd. ed.--Eddy Joseph. sd. rec--David MacMillan. sd. re-rec--Bill Rowe. sd. effects ed.--Alan Paley. p.assistants--Rory Enke, David Lamb, Lance Townsend. stunt co-ordinator--Jim Arnett. stunts--Gary M. Hinds.

I. p--Albert Finney (George Dunlap), Diane Keaton (Faith Dunlap), Karen Allen (Sandy), Peter Weller (Frank Henderson), Dana Hill (Sherry Dunlap), Viveka Davis (Jill Dunlap), Tracey Gold (Marianne Dunlap), Tina Yothers (Molly Dunlap), George Murdock (French DeVoe), Leora Dana (Charlotte DeVoe), Irving Metzman (Howard Katz), Kenneth Kimmins (Maitre d'), Michael Alldredge (Officer Knudson), Robert Costanzo (Lee Spinelli), David Landsberg (Scott Gruber), Lou Cutell (Willard), James Cranna (Harold), Nancy Fish (Joanne), Jeremy Schoenberg (Timmy), Stephen Morrell (Rick), Jim Lange (MC), Georgann Johnson (Isabel), O-Lan Shepard (Countergirl), Helen Slayton-Hughes (Singer), Robert Ackerman (Wailer), Eunice Suarez (Mexican Woman), Hector M. Morales (Mexican Man), Morgan Upton (Photographer), Edwina Moore (Reporter), Kathryn Trask (Nurse), Bill Reddick (Priest), Bonnie Carpenter, Margaret Clark, Jan Dunn and Rob Glover (Mourners)

11,127 ft. 123 mins.

Prizewinner at the annual Book Awards in San Francisco, writer George Dunlap makes the usual speech about wanting to share the award with his wife, "so aptly named Faith". Aware that George is being unfaithful to her, Faith subsequently quarrels with him, and has his bag already packed when he announces that he is leaving her. Their three younger daughters, Jill, Marianne and Molly, accept the situation calmly enough; but the eldest, Sherry, aware of his liaison with Sandy, a divorcee, is bitterly resentful. George moves in with Sandy, and tries to make up with Sherry by buying her a coveted typewriter as a birthday present. But she angrily refuses to see him or accept the gift. Meanwhile, leaving George resentful, an affair has developed between Faith and Frank Henderson, a handsome contractor who is building the Dunlaps a tennis-court. With the divorce proceedings under way, upset by the death of Faith's father, of whom he is very fond, George's anger is increased when he is treated as an intruder at the funeral by his mother-in-law. Afterwards, George and Faith quarrel drunkenly at a restaurant, then retire to bed together; he is hopeful of a reconciliation, but she insists she wanted him only because of her grief over her father. Aware of this incident and also suffering from a frustrated crush on Frank, Sherry hysterically accuses her mother of sleeping around, and runs away. Finding her outside Sandy's beach house, George tries to explain; and partially reconciled, she accepts the typewriter. George drives her home to find a barbecue party in progress to celebrate completion of the tennis court. Enraged by Frank's proprietary attitude, George bulldozes his car through the court and new patio. Frank contemptuously beats him up; and from the ground, George lifts his hand in appeal to Faith ...

Behind the credits, a mournful theme is picked over, single-finger style, on piano while the camera observes a misty landscape, the silent house, a bicycle wheel slowly turning, toys littering the porch, a swing-chair gently creaking, an abandoned teddy bear. Evocative images, redolent of desolation, yet effectively irrelevant to the film that follows, since this divorce ends neither in a deserted house nor in the children abandoning their happy games. The images are, in a sense, selling the notion of divorce as a desolation; and as in Midnight Express and Fame (although less destructively), Alan Parker proves all too anxious to puff the commodity he hopes audiences will buy. Bo Goldman's script, as one might expect after Melvin and Howard, is almost absent-mindedly undemonstrative at its best in simply observing the minutiae of marital familiarity. A throwaway moment, for instance, as the couple prepare to leave for the awards ceremony near the beginning of the film: he politely remarks that she looks pretty, she retorts that he sounds surprised and the shaft of irritation between them is jumped by an equally tiny spark that fires their bitter quarrel after the ceremony. Or again, in a different mode, a brilliant scene in which an embarrassed George, accompanied on legal advice by a comfortably debonair policeman to see fair play, arrives at the house to collect his share of books and chattels. Soon a despairing cry is heard, "Where's my Cassell's?"; "You left it in that terrible restaurant in Provence"; and as both burst into giggles, remembering "You always had such a pretty smile" - they are whisked irresistibly back into the sunny days of love and courtship. There are many moments like this in the film, probingly offhand and beautifully acted, especially in scenes involving the younger children (four sisters, for once really do behave as though they had lived together all their lives), who react to the divorce situation not so much tragically as with the mingled curiosity, amusement and disbelief of kids learning about the facts of life in the school playground. Again there is a superb exchange when Sandy, at bedtime, is faced with an awkward catechism by the girls: "Bet you want to make love to daddy?" - "Yes, I do" - "What's it like?" - "A rare and beautiful thing" - "But what's it really like?" - "Like eating ice-cream". One hardly needs the smothered and snort of "It's disgusting!" that follow her departure to realise that here is a woman who has no idea how to live with children. One immediately recalls, from much earlier in the film, a scene in which Faith and her daughters were united in a wholly adult playfulness at her dressing-table while she got ready to go out. As much as anything, it is probably an obscure awareness of this discomforting lack in Sandy that makes George cling despairingly to what he has lost. Parker, unfortunately, is not content to follow the script's lead, and embellishes it with in-numerable exclamation marks. Not only is there a beach house, so that characters can brood in picturesque solitude on the shore, but extravagant use is made of windows against which they can pose in forlorn silhouette at moments of crisis, usually bravely failing to stifle back a tear. Close-ups stress the moment of hesitation as a hand reaches for a door-knob; a succession of songs offers lyrics tautologically commenting on the action, emotion is so hyped in the visit to the father-in-law's deathbed that it looks comically as though George were trying to shake the poor man's last breath out of him. It is, in short, an Alan Parker film, complete with the characteristically overblown final sequence which drags in a burst of apocalyptic violence, ending in the tired cliché of a frozen shot as George reaches out his hand in appeal. Excellent performances from Finney and Diane Keaton, even though, in the circumstances, they look as though they were stretching the roles to surefire Academy Award-winning size.